This project was a fucking wormhole. I didn’t want to go down it but it’s gravity was just too strong.

It was also a perfect example of the engineering process and how it goes, for better and worse.

I started riding skateboards for real in 1984. I was 14. Sure, we played with toy skateboards when I was younger but that spring I had come across a real skate shop during a family walk in Boston, Beacon Hill Skate, and everything changed. I instantly knew I had to get a real ‘pro’ skateboard. Following that day, I worked for several weekends, single-mindedly getting the needed cash together, and then bought one. I got a Sure-Grip (SGI) “High Voltage” model. It was junk. I really should have spent a bit more money. Another $20 would have got me into legitimate “pro” territory but I was a kid, I was excited, and now I had a real skateboard. I rode the hell out of that board. That’s where it all started.

Interestingly, Sure Grip International is one of the largest producer of skateboard and roller skate trucks. Their house brand wasn’t good at all but most people have owned something they made at some point in their lives.

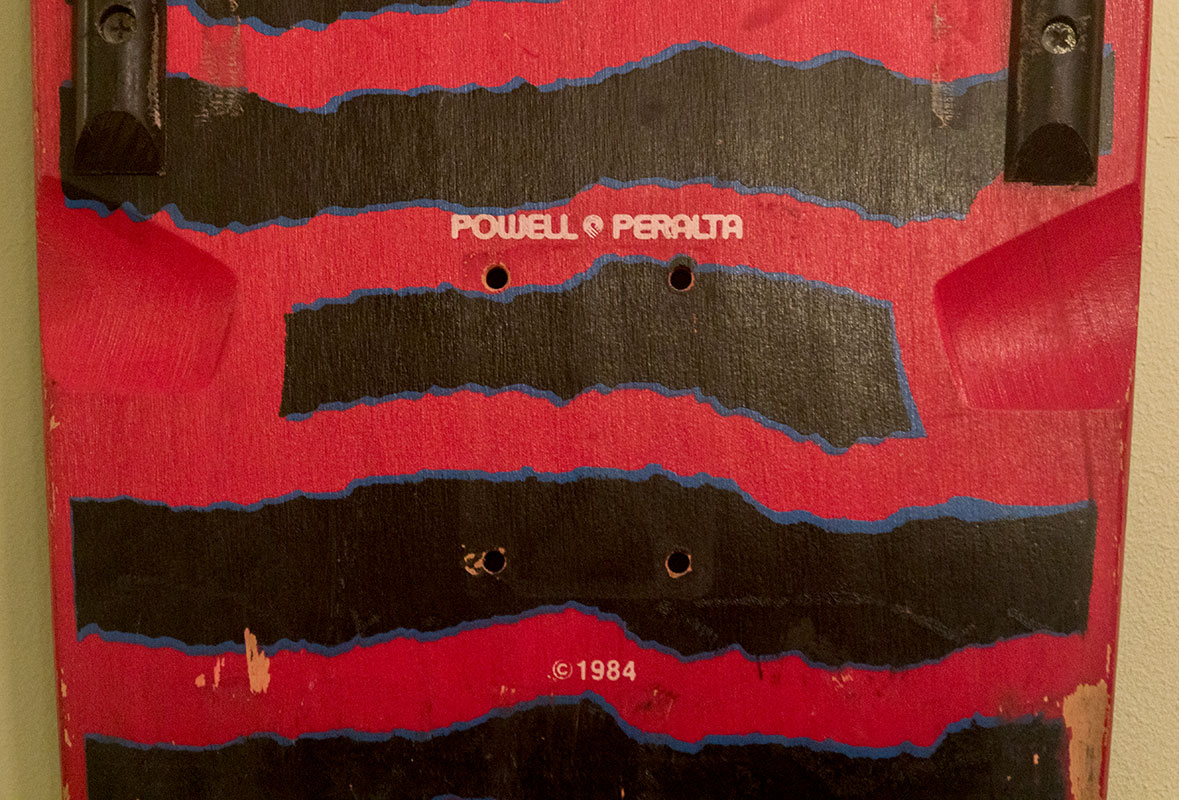

That skateboard had wheel wells. Everything did then (except for freestyle boards). Most of the quality boards for sale would be called 10×30 bombs. A generic shape with some graphics. Some even had the new ‘concave’ feature rather than a flat top. Boards were wide then. Wheels were 60-64mm in diameter and upwards of 50mm wide. There had to be some clearance just to allow for turning. That’s what the wheel wells were for.

As time when by, boards got side cuts, they got narrower, noses kicked, wheels got smaller, , concave deeper, and boards became Popsicle sticks. Somewhere in there, wheel wells disappeared. I’m sure jump ramps had just as much a roll in that as the changes in board designs. Regardless, they went away and nobody cared.

I retired from real park skating back in 2008. Since then I have continued to cruise around and travel with skateboards. I love them. I just don’t look to do tricks. Just cruising and getting around. I’ve been developing skateboards over time that are good for this. I re-cut shapes that work well. I drill new truck positions. I put a lot of thought into them. I hadn’t even thought of wheel wells though.

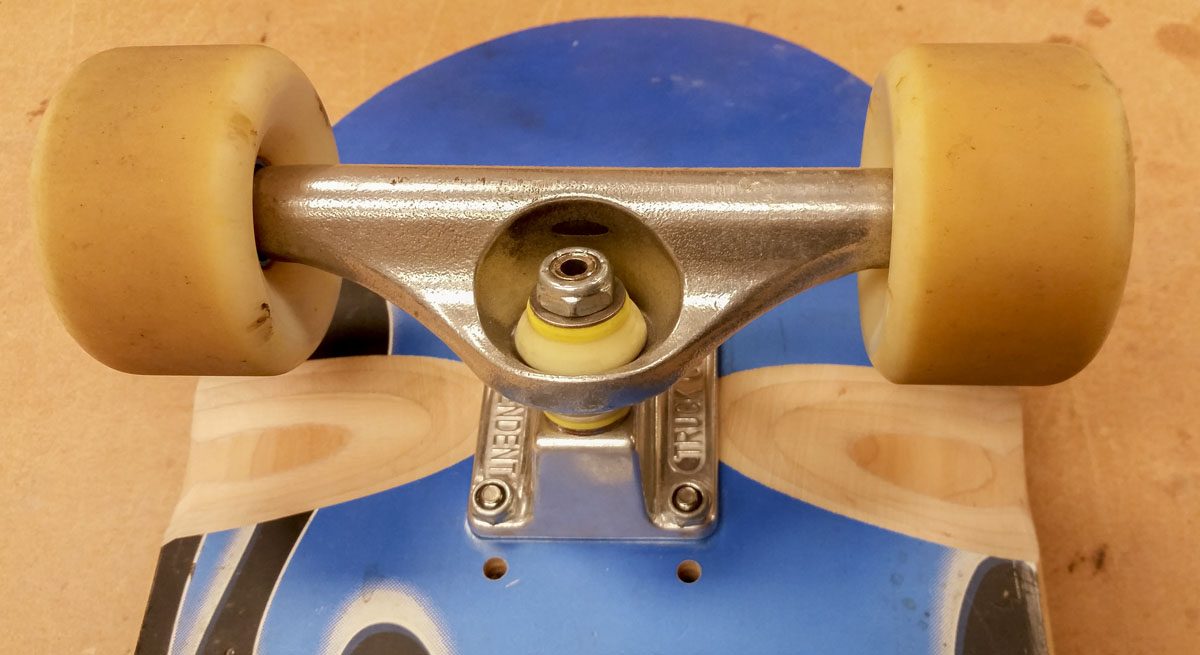

In a skateboard, we want the deck to be as low to the ground as possible. For cruisers, we also want large diameter (62mm minimum) wheels. These two parameters compete for space when the board is leaned over, and cruisers see pretty high lean angles. Thus, considerable time is spent looking for just the right amount of riser that gives us the turn we need but with just a trace of wheel bite.

I don’t know what it was last week. What caused it to occur to me. I was somewhere on campus. I had my board with me. Suddenly, I thought, “If I had wheel wells, I could get my deck a lot lower, larger wheels, or at the very least, a lot more turn.” It may be that I had grabbed a board that needed risers that day due to it’s 64mm wheels. There wasn’t a bit of hesitation, a new project began.

With wheel wells, even if I already have no risers, I could increase wheel size, which would be pretty cool. Some of my decks have risers, some don’t. I could always use a larger wheel.

I ordered up a 3″x3″ drum sander that would mount to a 3/4″ shaft. I’d figure out how to mount it when it showed up. Probably, in the lathe and hold the deck as I cut. I didn’t have great plans at that moment.

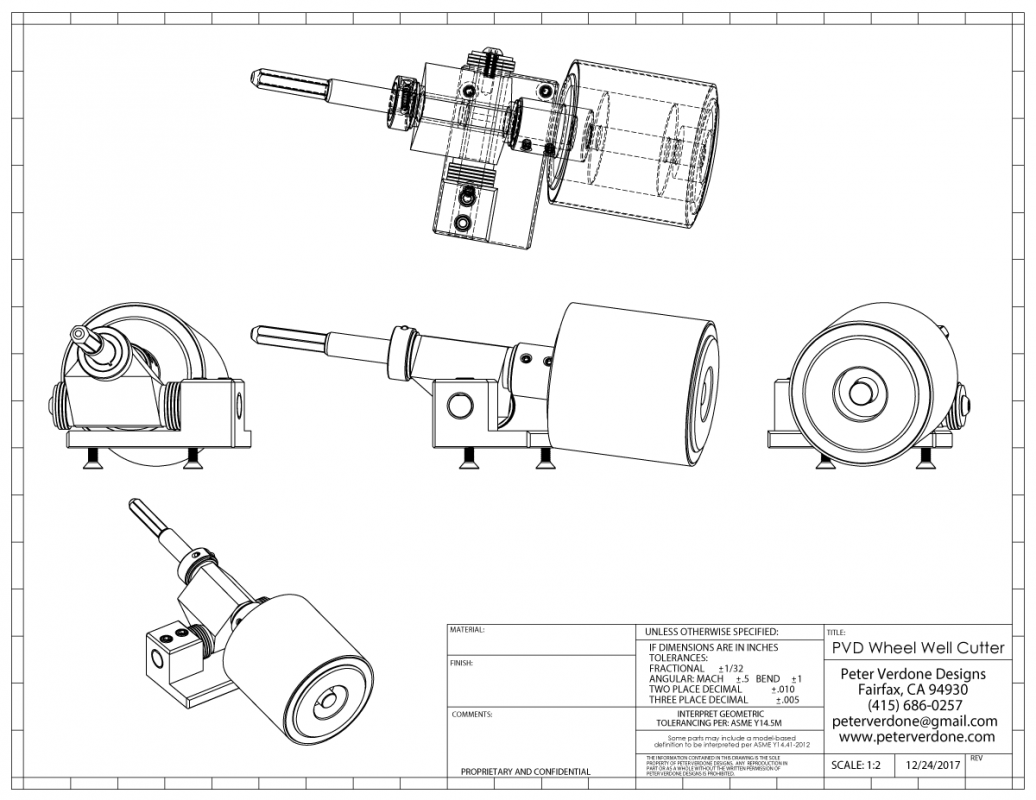

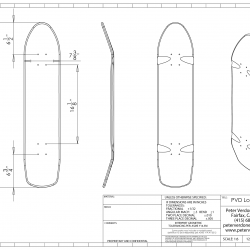

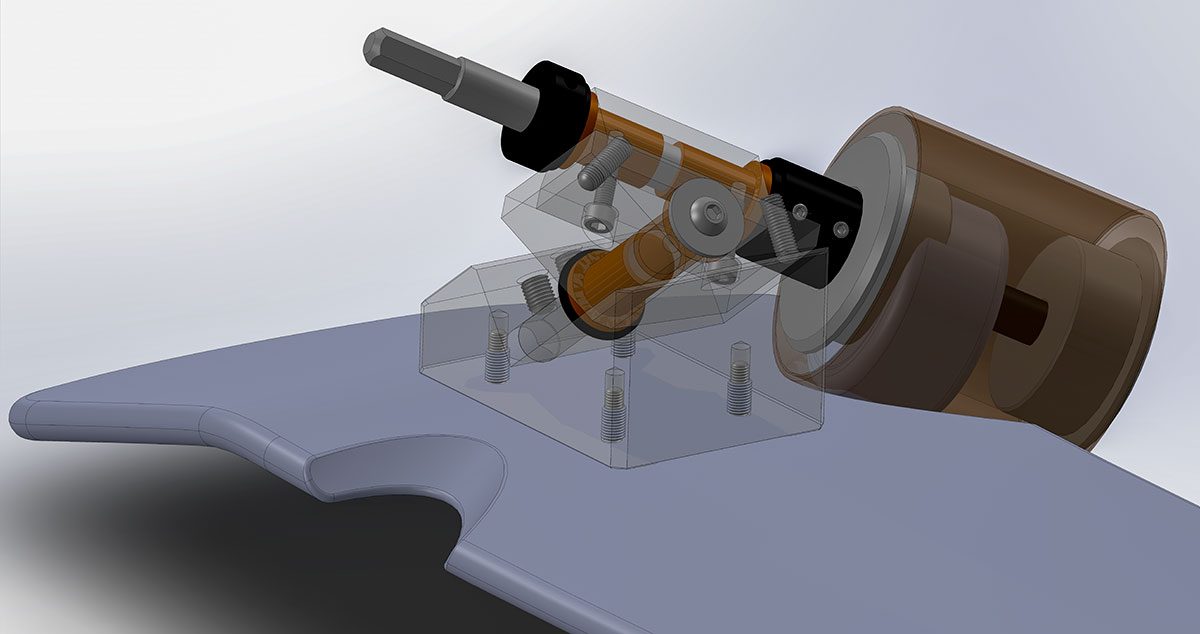

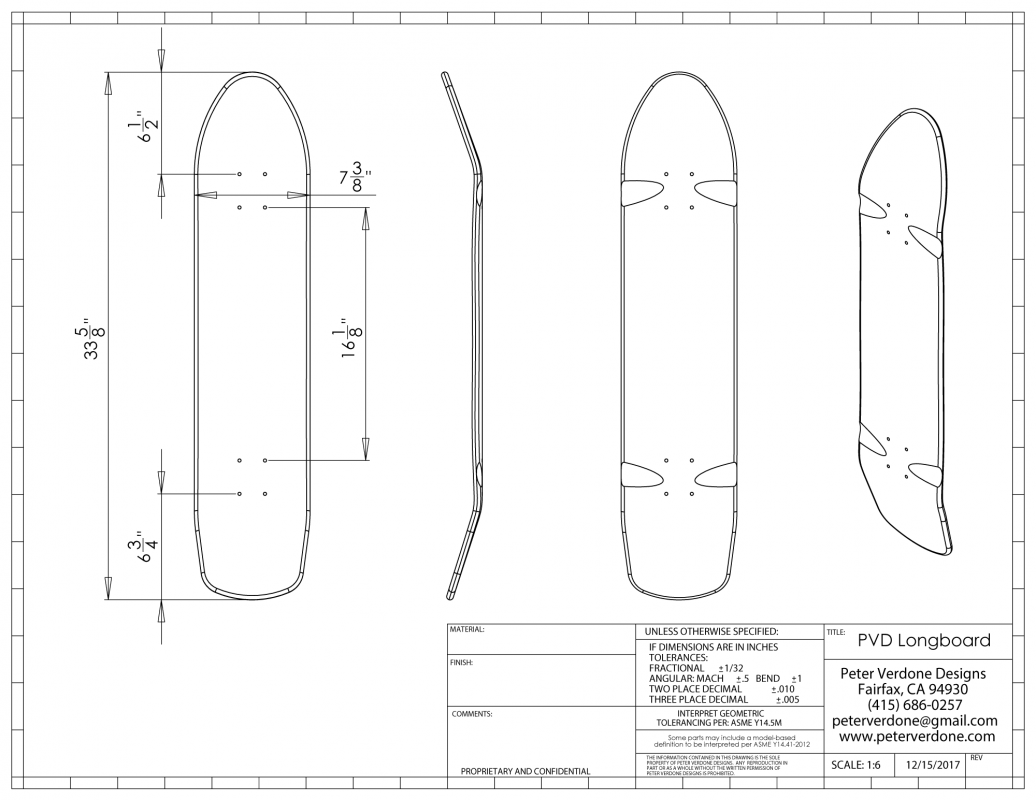

Because I’m who I am, I wanted a plan and a print. I got to modeling the system so I could very accurately and precisely place the cut. It took a little bit of time to reverse engineer a quality model that was flexible for whatever condition I wanted to apply. Wheel diameter, steer angle, and truck model would change things slightly. I factored all that in.

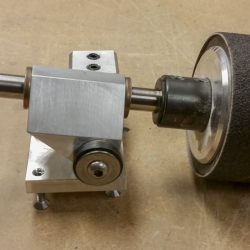

Ronen was hanging out after a mountain bike ride last weekend. We were in the kitchen and I was telling him about what I was up to. He gave me shit about using a lathe with an abrasive and my idea of free handing the cut. He figured I could make a fixture that would be better. I didn’t want to spend the time. By the next day, I decided he was right and some kind of tool should be made. This change of course devoured two weeks of my free time. Ugh.

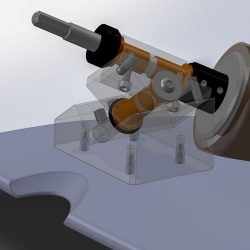

I wanted to create a tool that was easy to produce but also adjustable and well engineered. I reverse engineered some Independent Trucks I had on one of the boards in the office. I modeled exactly where the wheels would be as they contacted the deck. I then modeled a tool that took into account the diameter of a sanding drum that would cut just what was needed for the wheel path. I even included stops for the cuts. It was totally sorted.

I ordered components and materials from McMaster and I started cutting. Some improvements were added while cutting and the model was changed to account for the improvements. So there’s a little difference between the final result and the model show here.

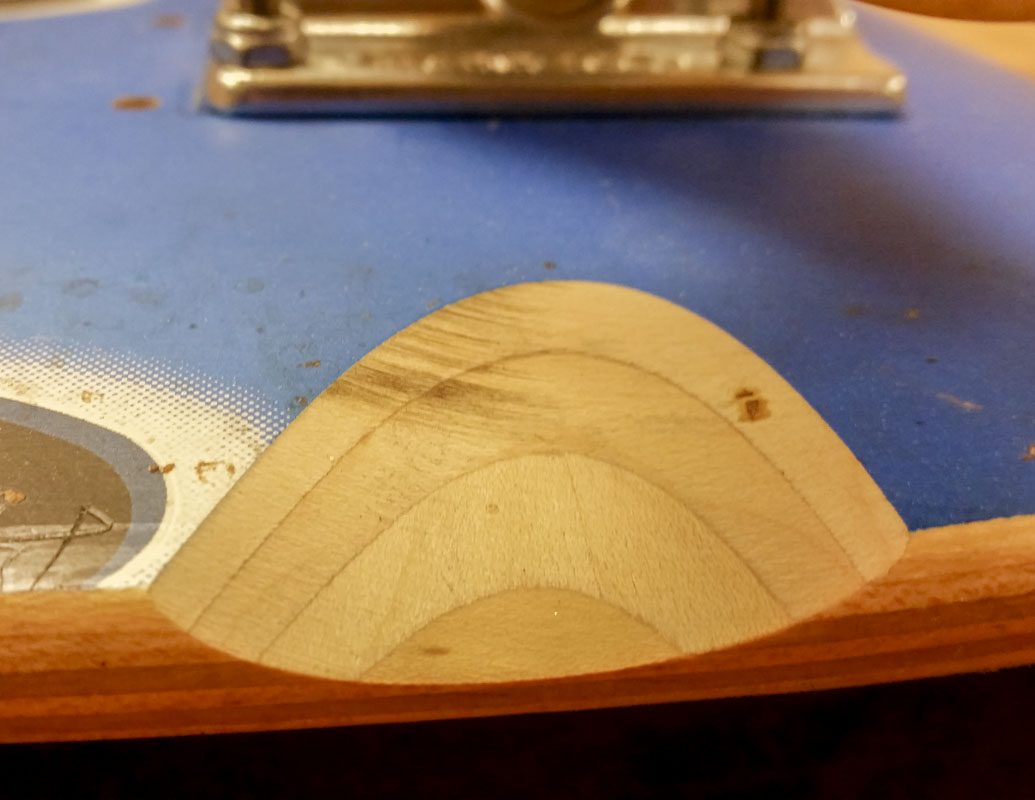

I used my old rain board to test on. The first round of cuts were a little off. My model was bad. I had made a pretty good error in the reverse engineering work that I had done. I went back, fixed the model, and came up with a band aid for the cut parts. It worked well. The next iteration was to be dialed as the model is a lot better now.

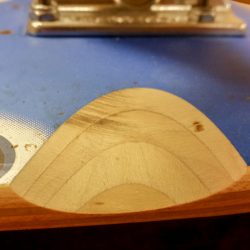

Second cut, pretty dreamy.

I had ordered 3″ x 3″ sanding drums of 120 grit. That grit is great for finishing the cut but not for hogging out the bulk. For that, 50 grit is a lot better.

Here’s the problem. While everything I did so far was correct and completely sensible on paper, it was wrong. It’s not right even though it looks right on the planning and engineering side.

Here’s why.

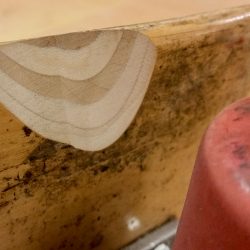

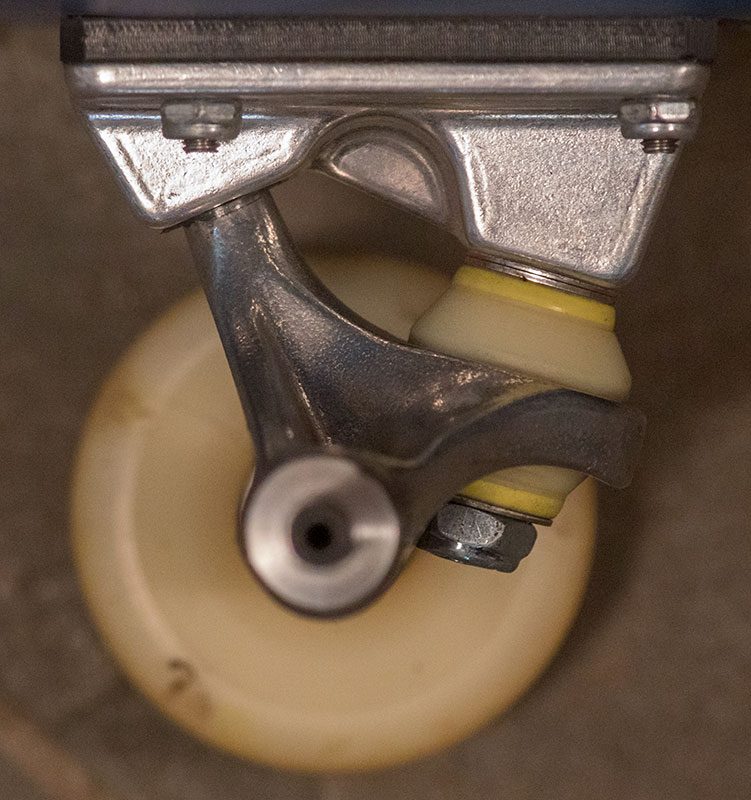

You can see here the wheel contacting the deck where I cut the well. I was really jumping on the side of the board to get the wheel to bite so don’t get the idea that this happened easily. What we see here is the wheel contacting pretty much exactly to the cut in the deck. The issue is that it only uses two layers of veneer of the cut. The other two layers of cut are doing nothing to help the wheel clearance although cut is limited by them, so I don’t start cutting over to the top side of the deck.

So while looking lovingly at the part and impressing friends and relatives with all my fancy homework, I get a pretty useless wheel well. The cut needed to be a lot flatter so that more of the deck is removed inboard. Then, 3 or 4 layers of ply will be cleared for the wheel instead of two. That’s a huge difference.

This is important in in engineering. Results. Little else matters. Are you solving the problem at hand? Being precise and accurate doesn’t do anything if the goal isn’t achieved. I wanted to make a tool that would be easy to use and maximize my turn without cutting more than halfway through the deck. The first approach didn’t do that even though it was impressive. The second does that but isn’t as flashy. Get results. Results matter.

All this sent me back to the drawing board and ordering more material. I simplified the fixture to instead of mimicking the true motion of the truck to form the cut, I went to a horizontal pivot and at 10 degree angle for the sanding drum. I lowered the cut angle to what would be a reasonable minimum and shifted the pivot away from the cut as much as the drum would require. Better still, I added the ability the fairly precisely place the cut along the length of the board. This helps adjust for differing truck geometries and wheel diameters. This design is so much better than the original yet so much more basic. Good engineering.

Obviously, I would like to have a 6″ inch sanding drum rather than a 3″. That would open up the cut a little so I wouldn’t need to be as accurate with my cut. The problem is that 6″ drums aren’t readily available and would require a bit more spending and engineering that I’m not interested in doing now. Maybe another time in the future.

I decided to go with a full length cut on this first board as I was interested in the aesthetics on the full width deck. I like the ‘wings’ look. On my sportier boards, I’ll do a truncated cut.

One important tool needed for this work is a corded 1/2″ drill. A cordless 3/8″ drill is quickly overwhelmed by the amount of work needed, running through batteries and overheating.

Now all I need to do is seal the board back up with some polyurethane to keep moisture out of the wood.

2/6/2018 UPDATE

Here’s how well this is working. 64mm wheels, no riser, full loose, full low. I had to really work to get a bite. Nailed it.