I hadn’t been to the Philadelphia Bicycle Exposition until this year. It was long overdue for me to attend as it is a very east coast event and I’m an east coast (originally) guy. Plus, folks have always said great things about the event.

Unlike NAHBS (North American Handmade Bicycle Show) which moves from one city to another every year, the PBE is in Philadelphia every year. Thus, a solid and regular contingent of builders and enthusiasts from Boston to Washington DC (the Northeast Megalopolis) and as far west as Ohio can easily attend in just a day of driving. If you haven’t looked at a population density map of the US lately, that about 20% of the people in America.

This was also going to be another first for me. I’d be giving a lecture at a major bike show. My topic, Modern Bicycle Design and Engineering for the Framebuilder. Clearly, there is a lot being promised in this title. My goal was to try to introduce to framebuilders a different way of understanding the problems and solutions that they are working with. A more productive way of improving the platform that we all love. What is engineering, really, and how do we go about doing it when working with bicycles.

I could get into specifics. I could give instructions. Who would that serve? If I can change the way people think, they could be the ones that are teaching me in a few years. Here’s the thing, I grew up getting a lot of bad advice and shitty guidance from many people that had no business giving it. They were ignorant, charlatans, or early students rather than masters. That was in the cycling world but even more so in the educational system. I can count on one hand the real masters that gave me a window into a way of thinking that moved me in meaningful ways. I wanted to try to at least approximate what that could be for someone.

Was my audience looking for this? I don’t know. It could turn into a rant or diatribe that just wasted their time. This could also be a perfect lecture but on something that they really weren’t interested in or didn’t resonate with them. How does this work?

Preparing for this lecture, I was full of anxious thinking. I’ve done public speaking at work and in various other situations but this was different. I was staking my name to a performance that could make me into a target for a lot of folks that enjoy bringing me down. Still… fuck the haters. I wasn’t sure if I’d be able to do a good job communicating all of the concepts that I’d hoped to, in an entertaining and engaging way, without the ability to edit and refine what folks would end up hearing like I do on my blog. It really is a live performance.

I spent plenty of time to get my ideas down and into some PowerPoint slides. My wife, Windy, helped me organize a bit and helped the slides look a lot better than they otherwise would. This was all new to me.

When I proposed my lecture to Bina Bilenky, the show organizer, we were able to agree that the end of the day on Saturday would be the best time for it. I knew that one hour wasn’t nearly enough time to discuss what I wanted and she fit me into a slot that would allow me to run late. Hell, I could do this as a 3-4 credit university class. It needed to be insanely compressed but it was still going to run long. The end of the day meant that we could go until they kicked us out, an extra half hour.

When the time came for the lecture, I was surprised to see that all of the seats in the room were full. It looked like only one or two people left during my talk and that they had somewhere else they needed to be. The dread of finishing to an empty room wasn’t needed at all.

While watching the video, it would be a good idea to look closely at the slides that are projected behind me. So that you can do that well at home, a PDF of the PowerPoint is available HERE.

A quick write up on the lecture was posted to the PBE blog, HERE.

During the lecture, in response to a question from the audience on the topic of engineering ethics, I mention a NASA flight manager that refused to sign off on the launch of the space shuttle, Challenger, in 1986 due to safety concerns of the seals and the cold weather. In fact, this was Allan J. McDonald, he was the Director of the Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Motor Project for Morton-Thiokol, a sub-contractor for NASA for the rocket booster motors. Following his testimony before congress on the cause of the disaster, he “was treated as a traitor and pariah by NASA and his own company”. This is the loss of status that we all fear.. but he is one of the heroes in this story and time has rewarded him for his actions.

This is an infamous case study in engineering ethics and worthy of review for anyone that is doing work that others count on with their lives.

You can listen to an episode of Freakonomics, Failure Is Your Friend (Ep. 169), where this is discussed.

The Feynman examination.

Another thing that I said wrong was my description (@11:31) of the origin of the Sturmgewehr 44. I say it was for “walking fire” which is obviously not the case as that was probably me thinking of descriptions of the BAR of 20 years prior. I should have said “intermediate cartridge”, giving the user much longer and accurate reach than a sub-machine gun and more off-hand control than a fully automatic rifle. There is a lot more to this but I feel bad about using such a fundamentally incorrect term while speaking off the cuff.

(2022-05-21. I talk about Sandy Kosman in the video. Sandy died today. He was a real bike legend where I live. I’m glad he can now rest. He was 80 years old.)

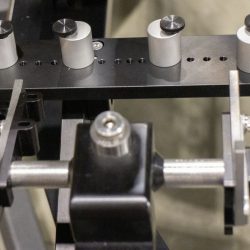

Because I was on the topic of design and engineering, and having a cast of characters, I decided to do another show of audio interviews like I had at 2017 NAHBS. I’d try to focus a bit more specifically on the design and the planning that folks were doing to produce what they had at the show. This, staying with my weekend theme. I belive that listening to these interviews will help the uninitiated see a little bit more behind the curtain as to how these bikes, parts, and tools are created.

***Audio note – some issues are showing up playing on my Android. Desktop seems fine. Working on a solution if you are having problems.***

Joe Roggenbuck, Cobra Frambuilding

Ian Colquhoun, Ignite Components

Brian Chapman, Chapman Cycleworks

Zach Small, Amigo Frameworks

Brent Curry, BikeCad

Gary Helfrich, Self

Rody Walter, Groovy Cycleworks

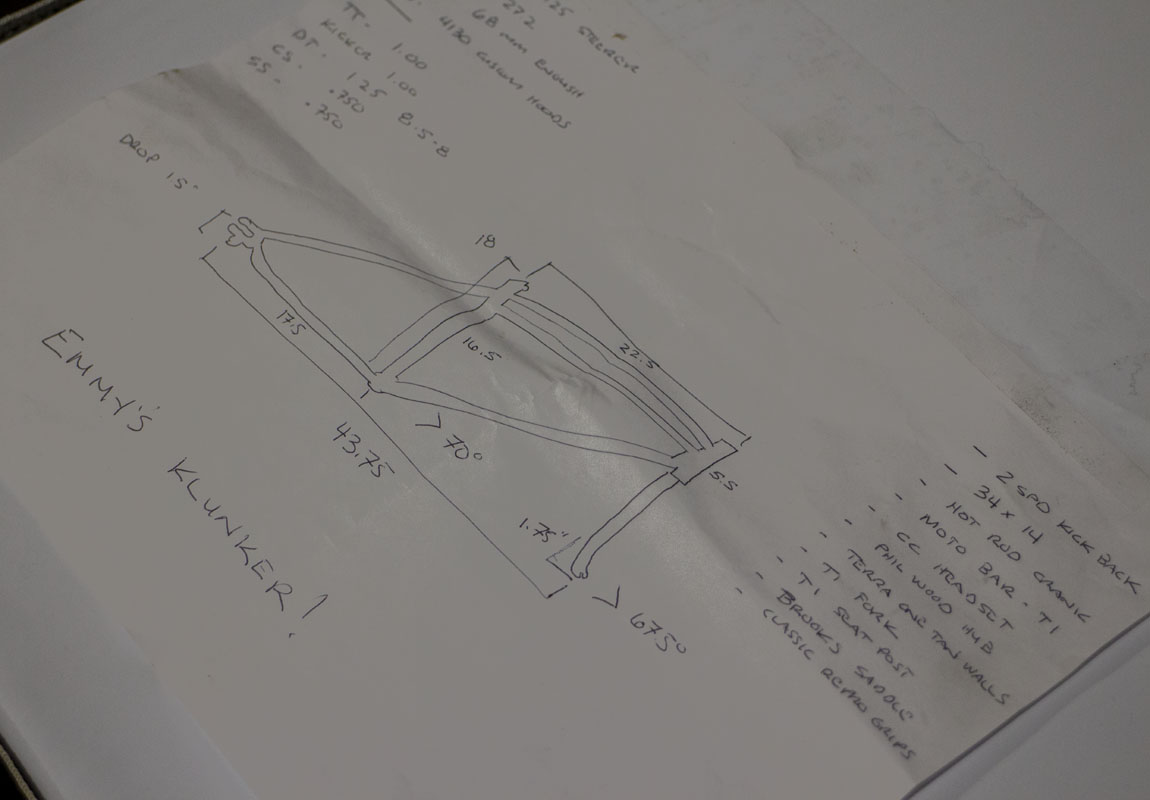

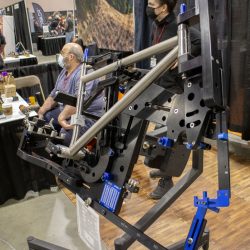

Without a doubt, one of the stars of the show was Rody’s (Groovy Cycleworks) klunker made for his adult daughter. Aside from some of the stellar details in the bike, what really makes this bike special is that it was conceived of 5 days before the show. Then built, painted, painted again, sourced parts and delivered to the venue. Doing that with a bike of this caliber is completely unreal and a demonstration of mastery that few can claim to posses. Notice, Rody had to fabricate the frame, handlebars, fork, cranks, and seatpost. He wasn’t happy with the first wet paint job so he did the painting again!! Dayum.

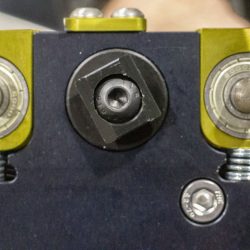

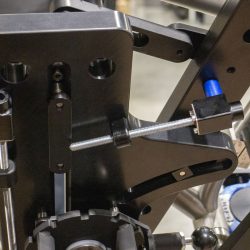

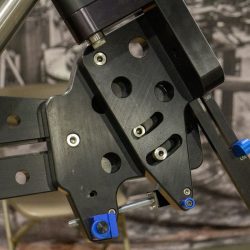

Another great detail was the steering lock on the Brian Chapman’s bike (Chapman Cycles) that we discuss in the interview.

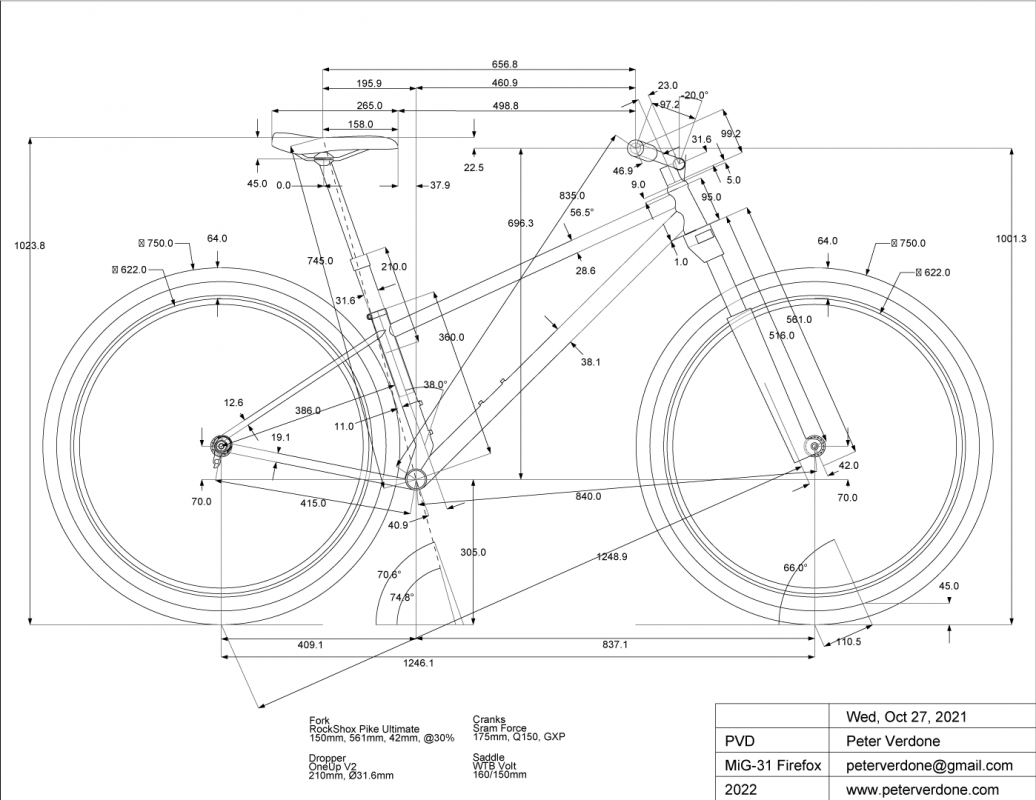

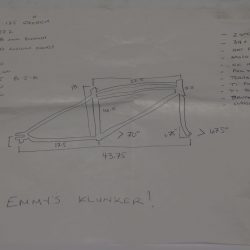

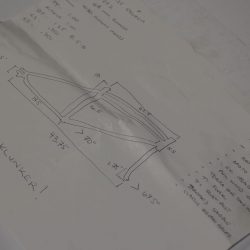

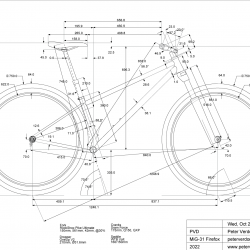

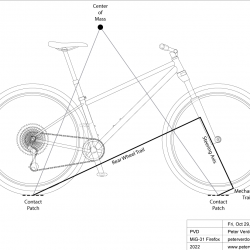

Two ‘prints’ were seen over the weekend if you count Rody’s chicken scratches. The other was revealed from behind a curtain while I was talking with another builder. This needs to change. Folks really need to start pushing for information beyond the Instagram if we are going to see progress with bikes. Going to a weekend at NAHBS or PBE and seeing 1 or 2 prints is utterly insane.

One cool thing that I saw on the streets of Philly near Rittenhouse Square was this mid-ninties BMW/Montague ‘Active Line’ folder. It seemed to fit within the PBE context so I’m sharing it as if it’s part of the show.