This bike was yet another journey into the creative pain cave. It was not something I had wanted to do. It was something I had to do. The war must be fought and we need the best tools. This is the magic bullet that goes around corners. Now, it’s inspiring further exploration in design.

This adventure probably began back in July while I was on another road trip to Whistler.

On that trip, I spent the better part of a day visiting with Ian Ritz at Chromag Bikes. Ian and I have discussed things over the years but this was the first time we were face to face, and on his turf. We compared my Blackbird with his Tomohawk and talked about a ton of other concepts in bike design. At one point, I pointed to a set of steel bars welded to a steerer binder. I asked if I could get some of the steel bars to try something similar. I couldn’t. Sad, but that’s how things go in this world.

Later, weeks after getting back from my trip, I was receiving a Diacro tube bender that I had lent out back from a local bike builder, Cameron Falconer. I was explaining some of the finer points of modern bike design and the “no fly zone”. He thought something should be able to solve the problem. I brushed it off. “Nah, it’s too expensive.” I was over-thinking things.

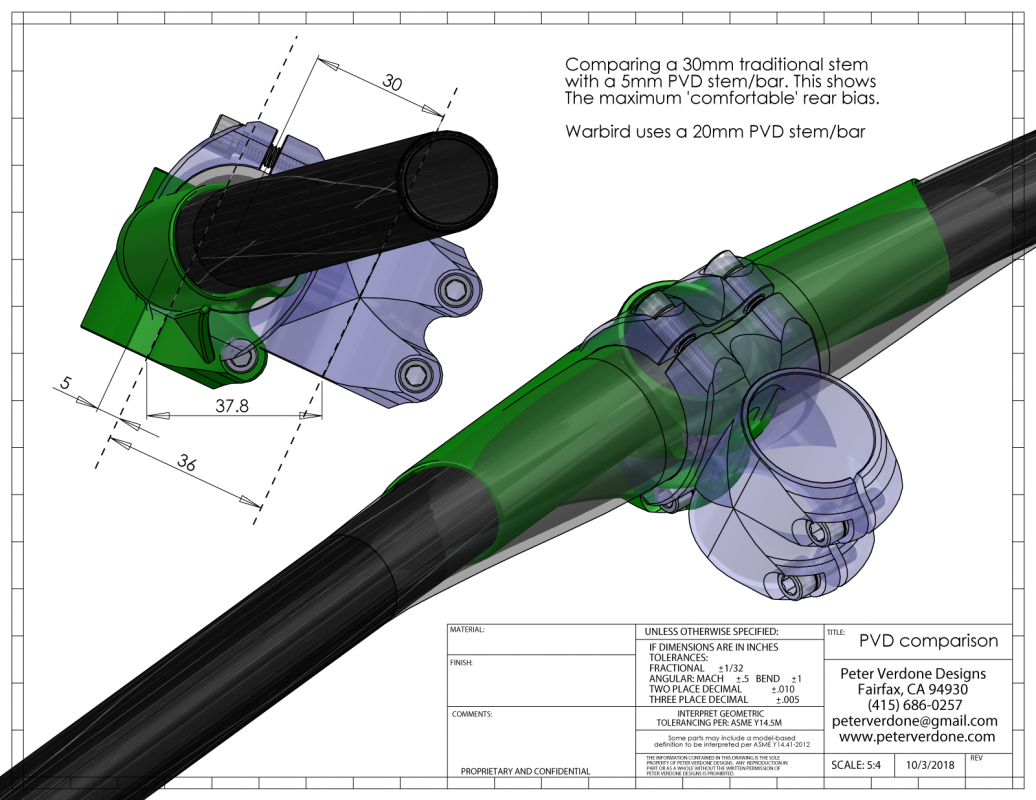

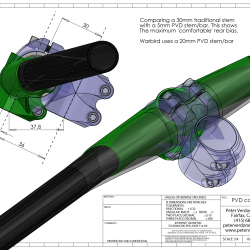

The “no fly zone” is just that, regarding bike frame geometry. It’s the difference in possible hand grip positioning of a forward facing 30mm stem and a rearward facing 30mm stem. 60mm totally restricting the layout of the front end of the bicycle. I didn’t coin the phrase. It was something that Sam Whittingham of Naked Bicycles came up with. Sam and I have been discussing modern frame geometry over the last few years and getting around the no fly zone has been an issue for us both. This mutherfucker was really holding the both of us back as we explore what can be done with Forward Geometry. I’m lucky to have folks like Sam to hash through issues and ideas that others don’t even know exist.

A few days after talking with Cameron, I was ruminating on a way to make this happen. I came on an idea. I drew it up. It didn’t work. I drew again. Garbage. No. So I went back to first principles. Starting from the grips and working my way backward. It magically appeared. I knew I had it. So simple. Getting around what we ‘know’ to what is ‘true’ is always a special moment.

So, just when I didn’t want to be building a new mountain bike, I was. I didn’t choose the timing. I’d have preferred to be building a motorcycle chassis. The muse made me do this. I am but a slave to her. I dove in to improve on the Blackbird and the Glamorous Glennis, to engineer a new way of doing hand grip mounts, and to incorporate that into a new frame geometry. I paid out a ton of money. I paid out a ton of time.

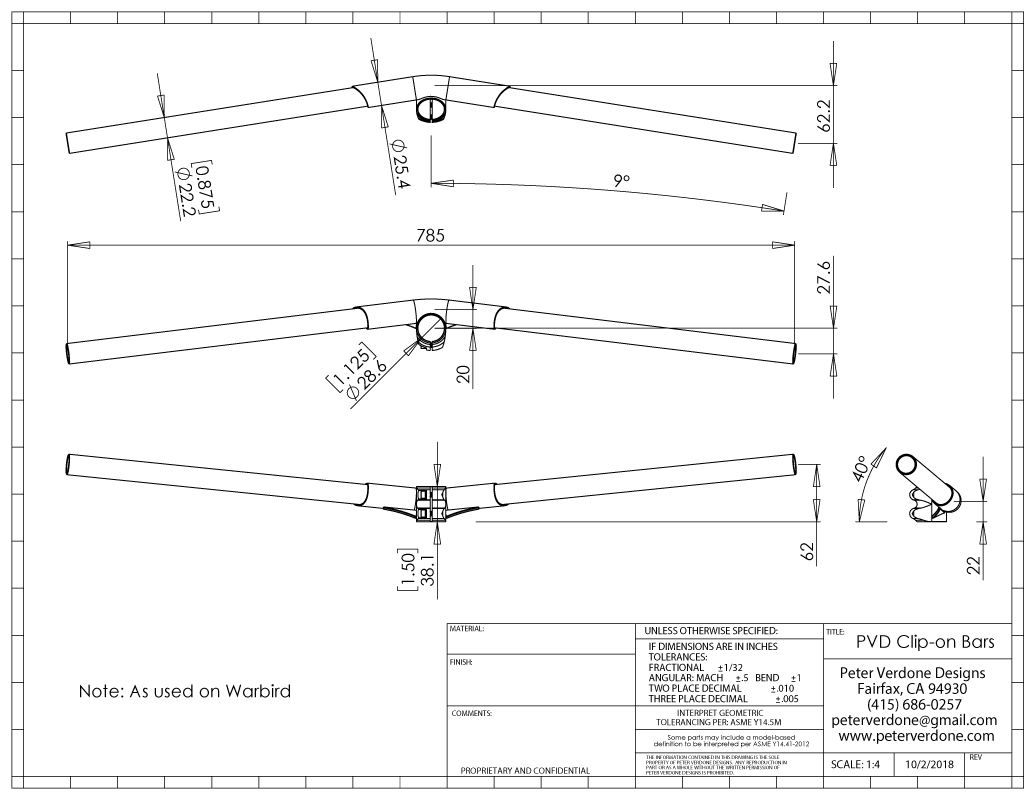

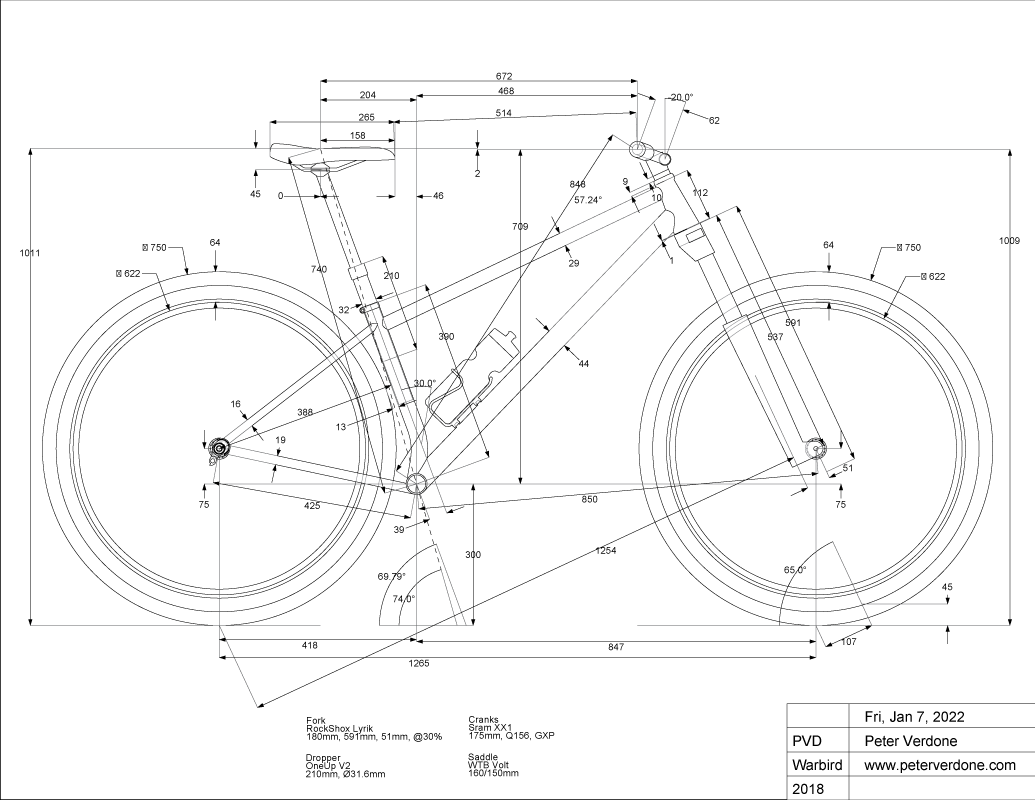

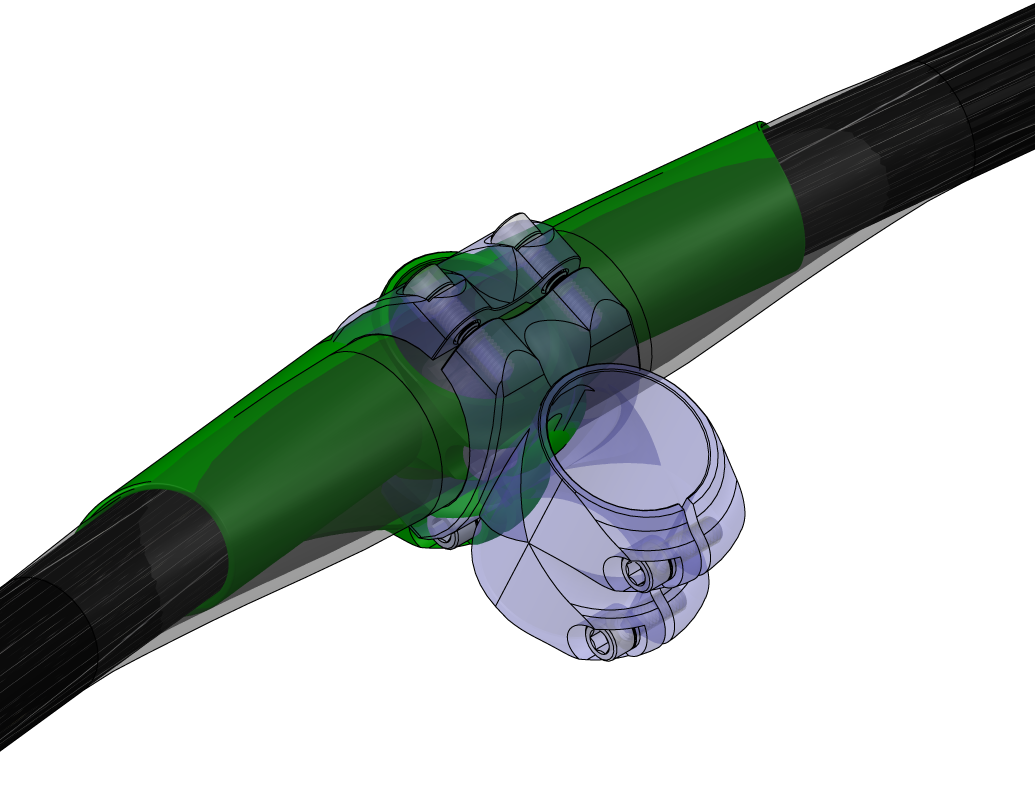

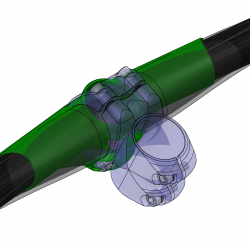

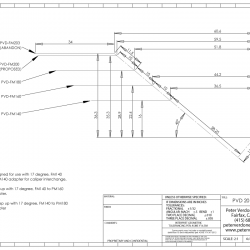

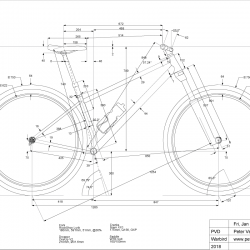

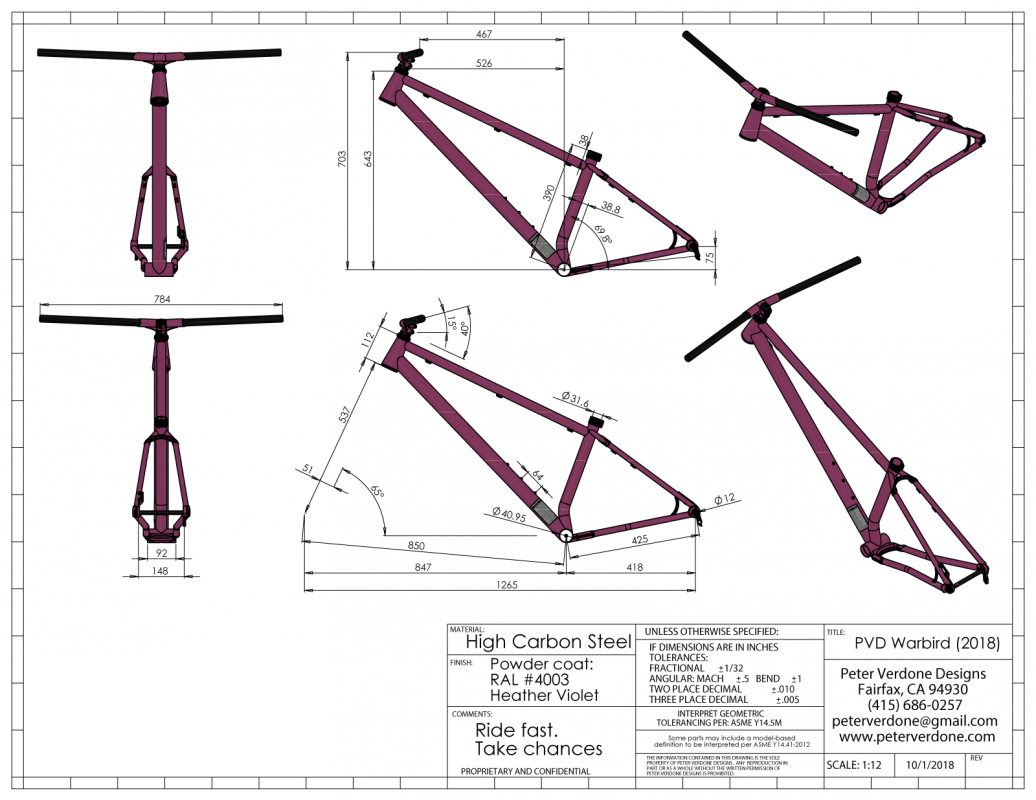

This bike was designed around the new handlebar configuration. The bars are different in a way that can’t be explored without a new type of frame to go with them. The shape of the bar starts from the grips rather than from the binder. The method that I use on this design allows for what would be known on traditional stems as a 15mm stem (a PVD +20mm), I needed room for adjustment for further setups. So I can easily build a similar setup that would be a traditional -5mm stem (PVD +5mm). If I were to go really nuts, I could just reverse the binder and work my way back from PVD +5. All of this while retaining the ability to adjust the height of the stem on the fork steerer. Complete liberation in design!

My nomenclature on the size of the bar/stem is based on the intersectional distance of the handgrip axii from the steering axis. It’s a pretty sensible and easy way of doing it for now.

So why not just slam it to 5mm? Well, there are lots of variables (and learning) going on here. 850mm of front center is a pretty big bike. Also, having 15mm of rearward design space allows me to have a second set of bars for pure shuttle fun rather than mixed trail. One thing I have learned over the years of bike design is that you need to leave room for all the uses of a frame even a few years out. All this will be discussed at length in the future, I’m sure.

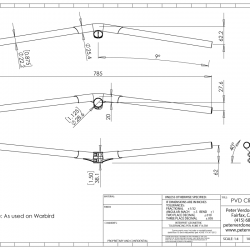

The graphic below shows a traditional bar and stem overlayed on the PVD bar/stem. The grip section of the tube made coincident. I think this makes the concept more explainable to most.

This type of handlebar can be forged, layed-up, welded, or machined from aluminum, carbon, titanium, or steel. There are many ways of producing similar results at many price points. That makes for a very inexpensive way of building carbon fiber into much of the part. Yes, it’s a little less flexible in terms of roll adjustment but elsewhere there are still open parameters, like height.

Of course, you’re saying to yourself, “I’ve seen this before…”. But you haven’t. Maybe you’d be thinking of the Syncros Hixon IC bar stem concept. You’d be wrong though. This bar, while novel in construction and superficially similar to mine, is not at all the same. It is merely a traditional bar and a traditional stem made one. The bend of the bar places the grips in the exact same position to traditional setups but with the drawback in lack of adjustability. The Sycros part was designed to cut weight and nothing more. My bar completely re-positions the grip relative to the steerer by re-imagining where the axii could be. (Note, I’m not talking about the sweep at the grip but the axis in the layout. ) Just like the Canyon CP01 (hover bar), the Syncros Hixon IC bar are a complete failure in understanding where frame design will progress. Just more part numbers that look at components and grams.

I’m 5’10”, a statistically ‘normally sized’rider. This frame has a fairly relaxed modern riding position that’s good for old and fat 48 year old guys. With that, it has an 850mm front center and a still responsive 65 degree head angle. No absurd seat angles or goofball head angles. A bike like this is simply non-existent anywhere but in my basement. A class leader.

To date, this is the most progressive and well-designed hardtail I know of. It’s on a whole new level of what can be done with front wheel placement and rider comfort. I’m in awe of it.

Carbon bars:

I’m excited about getting some more comfort into the frames that I design. This is a prototype/test design here but the direction is obvious: carbon fiber flex and comfort with custom geometry systems. It’s a cheap and easy method that allows for a huge range in design. It’s in prototype currently as every detail hasn’t been sorted but it’s being ridden.

These iterations have significant flex in them. They feel pretty great on trail. The question is durability. After some serious test time I’ll get carbon tubes on hand that meet the requirements of this application made for me to use. Tuning the flex to exactly the correct range for light and heavy riders would be cool.

Riding impressions on the trail is that while the bars are flexing significantly, it isn’t producing negative effects on steering or handling. As the flex is primarily next to the hand grip, it may just be producing comfort. It’s a very nice feel at the grips. I’m really loving this advance in my designs.

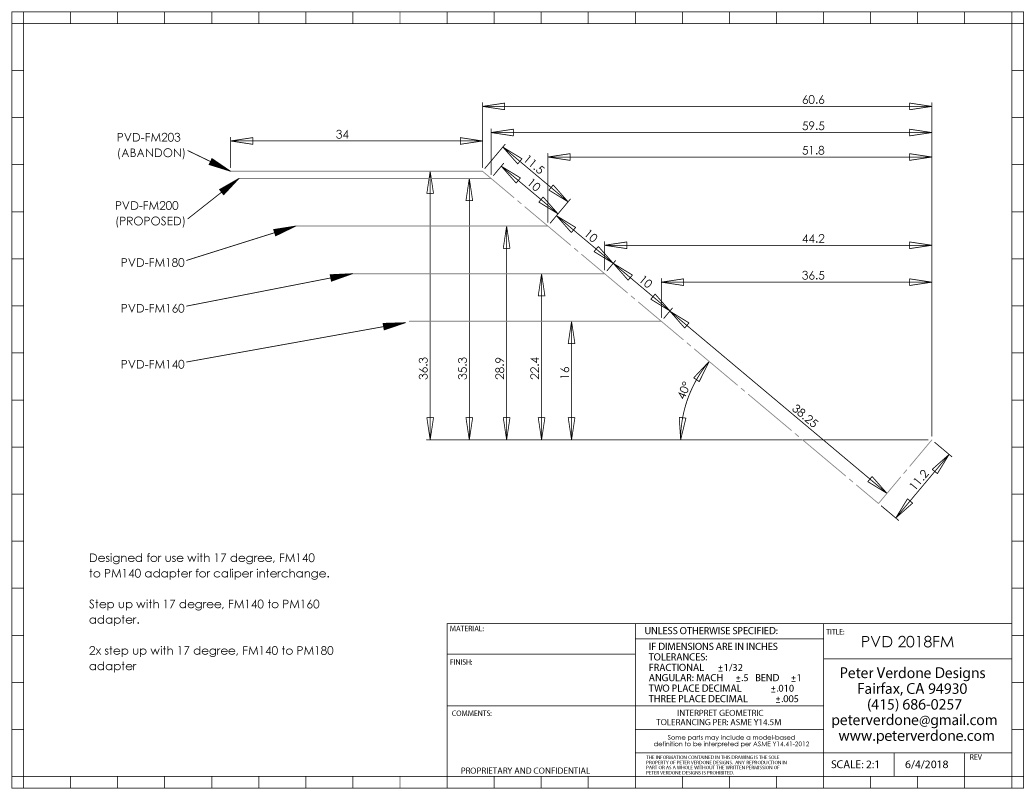

FM160:

For many of my mountain bikes of the last few years, I’ve used the PVD Stepdown IS mount for calipers in the rear. Clean and stiff. They looked great and worked great. Now, with the development of flat mount calipers in addition to post mount, the method needed a re-examination. This took quite a bit of work but the results will help not just me.

Others have proposed problematic specifications for FM160 and FM180. I solve the problem correctly and the proof is here. Stay away from the bad info. My numbers are good.

What is great about going in this direction is that I can use PM160, PM180, and PM200 (PM203 w/spacers) configurations until flat mount calipers being sold are capable of meeting the demands of real off-road riding. Current offerings are just not up to the job but that has nothing to do with the mount. They will arrive….and I’ll be ready. I can only imagine how much cleaner and tighter a SRAM Guide FM caliper will look. It may even allow for chainstay mount with a 180mm rotor.

Pink:

I’ve been wanting to do a pink bike for myself for a very long time. Really. There’s an old saying in cycling, “You’ve got to be a pretty fast mutherfucker to ride a pink bike.” My days of glory (not that I ever was a super fast guy) are long over. This bike though, is the shit. It’s dope. It’s so dope it earns the pink color on it’s own. RAL #4003 Heather violet w/ Axalta Crystal Clear PFC400S9.. I was really worried when looking at the swatches that it wasn’t going to come out an honest pink (too much magenta) but it really did. Seriously pink AF.

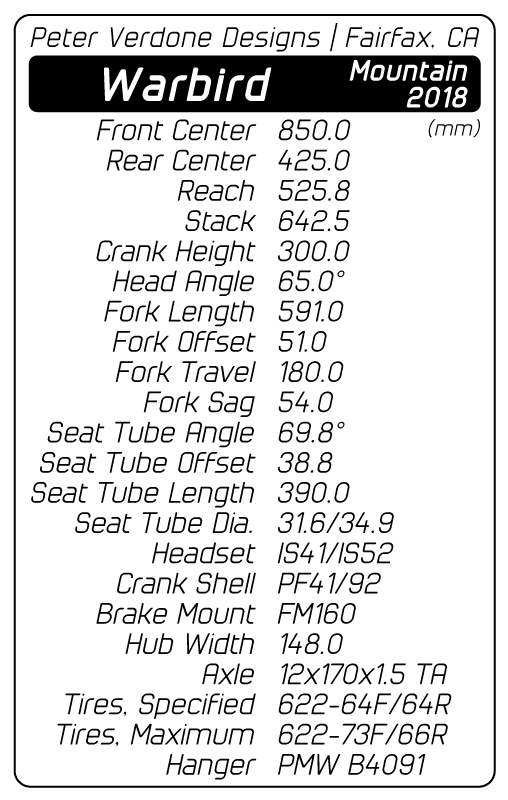

Data Plate:

I’ve been sorting out the data plates for my bikes but so far, it hasn’t reached prime time. It has now. The fabrication process has been figured out for the plates. The last detail was bending the part. I figured that out just at the last minute, a day before photos. I bent to the diameter of the down tube but should have bent to the seat tube. I’m going to move it from the down tube when I get back to working in the shop. This should be pretty easy now that a process has been sorted. I’m really excited about this as a data plate belongs with a real tool.

Data plate is shown here on the down tube. It was removed after photos, re-tooled, and bonded to the seat tube. The down tube wasn’t the right location for it but it was where I was with tooling at the time.

Seat position:

In mountain bike design, we have two different paradigms for seat position (or angle), hardtail or full suspension. A full suspension bike will sag out in the rear during climbs. Weight is moved over the rear end, loading the suspension. So the modern solution to that is to move the saddle forward. This helps during the climb placing the weight in a more advantageous position for power input and bike handling.

A hardtail doesn’t have that problem. The rear end remains in place going up steep hills. This means less change in the general ergonomics of the system. We have a forward seat position, but not as extreme as on a full suspension bike.

Crucial to understand are the costs of going too far forward on either bike. The problem is in traverse, or level surface riding. Here’s where the forward seat placement bites back. It shifts much of the riders weight onto the arms. A well placed saddle on a hardtail will feel good on climbs and in traverse. It won’t wear you down or make you sore when you have to cover a lot of ground. The full suspended bikes with aggressively forward seat positions will feel pretty horrible on flat surface and over time. This may not be a factor for riders in the Pacific Northwest but I probably is in many parts of the world.

The new framebuilding problem:

This frame pushes the limit of what I can do with the 660mm 1.125″ tube on the market. It forces me to contemplate having to use a 1.250″ tube even though I don’t think that is needed here. Still, we only have a 670mm (Columbus Zona), 680mm (from Nova), and two 710mm (Vari-Wall Chromoly), and two 720mm (Vari-Wall Thermlx) tubes to choose from on the market. These will work for the foreseeable future, but the options are a bit slim.

It’s time for folks to now put some pressure on their suppliers to offer what will be needed.

I may also look into just using 1.125″x0.035″ 4130 on another build if I need to.

Philly:

This bike is being released to the public just prior to the Philly Bike Expo, the Chris King Open House and Builder Showcase, and Fairfax’s Biketoberfest. I’m hoping that it will initiate some discussion among the folks on where progressive design is going and where smaller builders can compete with the bigger players. This seems to be what most folks are missing.

What is a modern hardtail? This bike has a 6mm longer front center than a 2019 Commencal Supreme DH 29. The same front center as a medium Pole Machine , but without the overly slack head angle and super steep seat tube.

But this bike goes uphill better than any enduro bike. What more could you want?

Thanks:

I need to thank many people for helping make all of this happen; Devin Bodony, Mark Norstad, Ronen Sarig, Nick Heys, Tyler Evans, Brian Berringer, and many more.

The Name:

This bike takes the name of a 2010 bike of mine, the PVD Warbird SS. At the time, it was very progressive. It’s not an antique. History’s dustbin. Like the Bird of Prey, I needed to bring some of the more awesome namesakes back into service.