It was Thanksgiving a few days ago. Thanksgiving is one of only a few real holidays in the United States and it’s probably the most important. Important, as it’s not about turkey or shopping or even your crazy aunt and uncle. It’s about gratitude and that’s some good shit. I always try to focus on what I’m thankful for and how lucky I am in the days surrounding the day.

I feel that I’m at a very special place in my process as a bicycle chassis designer. A master. It took an amazing amount of work to get to this point but it’s proving to be even more work staying holding on. Every day another onion layer is revealed to me and the work to get past it is daunting. A new discovery can often lead to a rebuilding of the whole portfolio. I’m exhausted by this but excited by it. It’s fascinating. There’s so much more to learn!

Nobody gets to this point on their own. We all get help, if in no other way than knowing some special people or just getting hired for the right job. We see the world differently because of these people and these opportunities. They are our mentors. They help show the way weather they know it or not.

I’m going to talk about some of my mentors and folks that made a meaningful impression on me.

Kenny Deutsch (Zito) – There are probably hundreds of (now) men like me that can look back at their life and remember ‘Zito’ as being a major actor in their life story. He touched a lot of people’s lives at a time when and in a way that they probably needed it the most. Zito came into my life when I was 16 years old, actually, I came into his life. He owned a little shop, Z.T. Maximus Motorsports, on Massachusetts Avenue in Arlington, MA near the Cambridge line. He had recently opened it to house his kart racing business and hobby. On the side he started selling skateboards and some other junk to help pay the rent and costs. Skateboarding was pretty small time in Massachusetts back then so we skaters always tried to find every resource we could. I was living in Lexington and Arlington was right between there and the killer spots in Cambridge like the C-Bowl, Turtles, Harvard, and a bunch of others.

So, I stop by to see what was up. Kenny was this 6’5″ (?) former basketball player and a total kook. He had all this rasta type stuff around his shop. He dressed like a slob and wore a mustache (often with food stuck in it) and workshop apron most of the time. Between the chainsaw-motorized scooters, machinery, kart tires, junk, and race karts in the back, it was the oddest retail experience most of us had ever seen. The few skateboards and parts for sale weren’t impressive or vital. Then Kenny would start talking. What-the-fuck?! This guy would start talking about all this crazy shit. He’d been around. Crazy 60s and 70s shit, NCAA college basketball, weird music, philosophy, kart racing, 2-stroke engine tuning, business ownership, and whatever else he was reading about. It just went on and on. It might have been left there but there was something that made it all stick; down in the basement, he had let a couple of the local stoners build some skate ramps. They were horrible ramps in this dirty shop basement. This being New England and Arlington being close to all the action, the cold, snow, and rain would push us to any place we could skate. We’d end up in Zito’s shop basement a lot.

Over time, it grew on us. Various personalities would be there; Jeff Shank (The Alien), Ram Hannan, Kevin Day, Estabrook, Eastie… It became this odd scene with Zito as this kind of circus ringmaster. There’d be these sessions after school or on snow days and we’d rest upstairs and hang out with Zito. He’d be tuning his kart, preparing for the next race, or we’d just end up getting high. We got high a lot there. It was known. Zito would talk to us about some strange philosophy or describe why stinger exhausts have the shape that they did. He’d be milling parts or welding something and we’d watch and talk about it. It was a crazy little world.

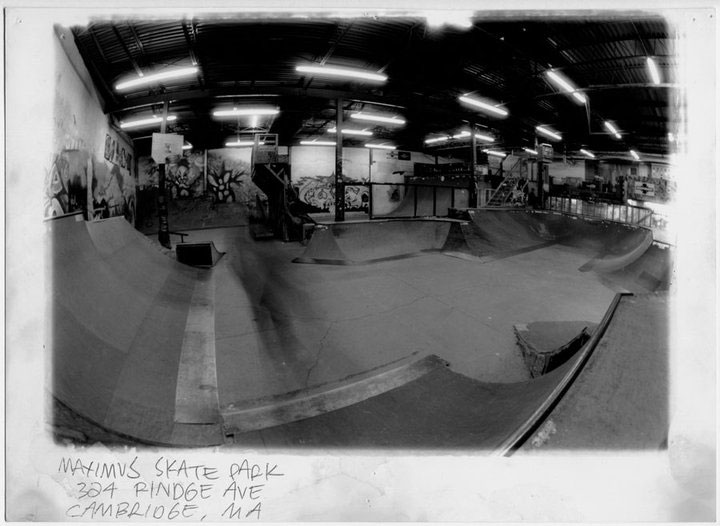

This being 1986, the skateboard boom was just starting to explode. Every week, more and more boards would be on the wall. The cases were filling with wheels and trucks. Things were getting crazy on the skateboard side. Zito and Jeff concocted this plan to get a warehouse and build some real ramps there and run a shop out of it. The first location was initiated but ended up stillborn, something about the fire department or zoning or something. Still, it became a repository for a bunch of wood from a few older ramps in the New England area. A new location on Rindge Ave in Cambridge was found, in the industrial lot right between two of Cambridge’s worst housing projects but across the street from the C-Bowl. Easy off or Route 2 or the Alewife Station. The location was amazing, it was dangerous, it was totally freeing. Lots of kids were mugged going in and out. The thing about this time was that skateboarding was treated as a crime in general, we were derelicts. At this location though, across the way from two chop shops and in the middle of a high crime area, nobody cared. The police would cruise by and couldn’t care less about a bunch of white kids getting high in the parking lot or the warehouse that had become a skatepark.

Over the years, Ram and I would fix our motorcycles at Maximus and Kenny would let us borrow tools and show us how to rebuild a carburetor or replace a drive chain. Ram rebuild one of his motors. Jeff would replace his transmission in the lot. We were able to do almost anything at Maximus. It wasn’t just that though. Many of us weren’t doing too well outside of Maximus and it was our safe place to go. Zito, Ram, and I would be there on most Thanksgivings or Christmas days. It was our home and it was for others. If you were tripping balls or couldn’t go home, you could crash out on the couches in the loft lounge behind the half pipe platforms, you could get your shit together before you went home. Zito would probably talk you down and set you straight. He didn’t care for us but he gave us a place and guidance.

We built the park into one of the major east coast skateboarding hubs of the 1980s and 1990s. Jeff as forman and designer, I got coping bent and welded, and everybody would volunteer and build and manage. Eventually, Kenny needed to retire to race out of Florida and sold the place to Ram and Doug. They kept it going for a bunch more years. It was the greatest club house we could have imagined and it was Zito that fostered it.

Zito gave so much of himself to all of us. He taught us thing we needed to know. If it weren’t for him, the would wouldn’t have been as good of a place for a lot of people.

Chris Chance – I had failed out of college and was a bit of a mess. It was 1990 or so and I had worked as a bike messenger for a year in Boston, a lot of my closer skater friends had gone to work on bikes so I had ended up there also. The economy had tanked and I was looking for work and nothing was working out. I was killing time at Maximus, probably fixing my motorcycle when Kenny mentioned that he knew Chris Chance’s wife and I should try to get a job at his bike business. I gave it a shot. I rode my motorcycle down there and asked to talk to the production manager, Bill?. I pushed hard to get that job. Around then I was in a motorcycle accident and broke my back. I think it made an impression when I showed up again on crutches and a brace saying that I still wanted the job. I got it.

Fat City Cycles was a crazy place. It was full of characters and personality. Artists and rockers and shredders all mixed together to make Chris’ bikes. It was in this tin shed by the train tracks at the edge of Union Square in Somerville. The place was full of old machines, welders, and a paint shop. It wasn’t glamorous in any way but it had tons of personality.

What makes Chris such an influence to me isn’t his designs or really what he did with bikes. I don’t think that he had much to share regarding that. What it was that he was passionately committed to producing the very highest quality bicycles that were possible and that he allowed an environment that gave a wide berth for the creativity and side interests of his employees. Many folks could be found in the shop after hours or on weekends working on a side project using the tools of the shop. This doesn’t happen everywhere and the names and businesses associated with Fat City Cycles is a long and storied one.

I learned a lot about being proud of my work and doing my best at Fat City. I was just a young guy with nothing much going on and this place and Chris’ leadership got me to see new possibilities and a trade.

Chris & Dale Hawkes – Business wasn’t Chris Chance’s strongest suit and the whims of the marked became to much. The company was over extended and couldn’t make payroll. It was shutting down. Fat City Cycles had been sold to Serotta and was being packed up to go to New York. I was there putting things in boxes and breaking down tooling. I needed another job and I didn’t know what to do. I knew I liked working with metal and making things, so that helped. A bunch of people from work had met at our house on Spring Hill Terrace once the news of the closing of Fat City hit us. They wanted to start another company, Independent Fabrications. Out of all the folks in the room that night, only Gary Mathis and I decided to not take part in the venture. This turned out to be one of the best decisions I ever made. I would have wasted 10 years of opportunity and experience if I had joined.

So, I’m packing things up at the shop. During lunch on one of the very last days, I sit down with the yellow pages and start cold calling machine shops in the area. I was asking if they were hiring or looking for apprentices. I got turned down by a bunch but this one guy, Chris Hawkes, said to come on by. They were in Arlington Heights by the bike path at the time.

I show up at Dale Engineering. It’s a machine shop with (at the time) a few CNC mills and a few more CNC lathes. They tell me about what they did; very high tolerance work with exotic metals. I’d have to learn how to read prints, measure my work, and code the machines. The work was making very challenging parts, about 30 at a time, and I wasn’t supposed to make any mistakes. I had to stand, never sit. No music. Bad coffee, and keep everything clean and professional. It was very strict, not in a punishment sense, it was the expectations. This was a no bullshit and very serious working environment.

Chris was Dale’s son. He was running the shop that his father had started. Dale was an OG machinist and knew all the tricks. Chris knew the computers and CNC methods in addition to all that Dale had taught him. They were both very very good machinists and the work they did with their crew was amazing. I was the ‘kid’. I knew that they were giving me a shot. They were starting me off from nothing to teach me everything so I busted my ass for them. I spent about 2.5 years with those guys. I came out of there a machinist and I could program real machines. Without what they taught me about rigor and the trade, I wouldn’t have been much. Also, I never asked Chris for a raise. He just kept giving them to me. That says a lot to an employee and I worked my best.

I was getting itchy and needed to leave the area. I packed up a van and drove off. I was looking for something the Boston Area wasn’t going to give me.

Marc Salvisberg – After a stint in Durango Colorado, I ended up in San Francisco visiting my friend, Gary Mathis. He was on Kevin and Dave’s couch living the skater life. I was planning on passing through. I met another friend and got to stay on her back porch for a bit. I was starting to like SF so I figured I’d make some more cold calls and see what kind of work was around. I had learned to work as a motorcycle mechanic while I was at a Honda/Yamaha/Arctic Cat dealership in Durango so I figured I’d try to get with some racing programs. I called Factory Pro in San Rafael and Marc answered. He said to come on by. I was really not the level of mechanic or prototype machinist that they needed but Marc hired me. I think it is because Marc was focused on bicycles personally and that was my strong suit then.

I learned some about motorsports while working with Marc. I learned to do engine machining with some very primitive tooling. This isn’t really about what I did while there. Mostly what I saw was a mad scientist working tirelessly on discovering the secrets of power production in a motorcycle engine. Marc would try almost anything. He’d run the dyno all day if he had to. He was going to figure the puzzle out and it was a sight to behold.

At some point in all this, I was busy making the 20th or so change to a carburetor for a bike and Marc was waiting for it for another run. He noticed my disgruntled and frustrated state from the dyno room, slid the window open, and asked “Pete, what are you doing here?” At the time, the question seemed stupid “I’m tuning this fucking bike, Marc.” I realized the point of this exchange years later. Marc wasn’t at a job but I was. I was punching my timecard and doing my time. Marc was working on a problem. A very interesting problem and I was just going to work. I left Factory-Pro a little bit later. Off in search of better money and a less harsh environment. When I finally understood Marc’s question, I was shaken. I hadn’t understood any of it.

Andy Graham – I left the motorcycle business to go work at a motion control industry job in Rohnert Park, Compumotor. It was a division of Parker Hannifin, a Fortune 200 industrial company at the time. I landed a gig as a toolroom/prototype machinist. I was on it and did a pretty good job. I worked with two other people but one stood out. Andy Graham. Andy was a musician and fabricator. He really wasn’t about precision or math or the fussy stuff. He’d just go to work on some problem and cobble something together. His work was amazing and he was always very creative. I always joked that the math was what was holding him back, but I was wrong. Nothing was holding Andy back.

Andy had an amazing portfolio of work that he’d done since high school. Musical instruments. One man band stuff. Didgeridoos and percussion stuff. Strange stuff. He was consumed by this thing that kept at him. There was something there. He was going to find it.

Years later, Andy did find it. He invented an instrument that was special, the Slaparoo. It was new and it worked. He eventually made that his full time job and is pretty successful with it. For guys like us, this is the dream and it happened to Andy. I’m jealous of him but he deserves so much success.

Kirby Bunas – About 1999, I left Compumotor after finding out just how incompetent most engineers really are. I figured that if these clowns can get paid twice what I do for half the smarts, I should get in on that myself. I went back to school to get an engineering degree. I had to do a bunch of math and physics at the local junior college and then finish up at the university. Santa Rosa Junior College was the best in my area so I enrolled. It had a stellar reputation at the time and I found that to be true. Real college work. They had a math department there that was designed to break you in the first semester or two. They didn’t want to waste their time with you unless you were serious. I was. I show up on my first day to find that I had Kirby Bunas for Calculus I. Kirby was said to be the toughest instructor in the program. Just my luck.

It was true. Kirby was tough. It was brutal in her class. I think we started with 38 students and ended with 6. I think I cried one time doing the homework one time. I doubted myself in the middle of it all. The thing was, as rigorous as her class was, Kirby LOVED the math. She had so much passion when she explained the concepts in her class that we got infected. Those of us that finished that class were at war. We weren’t just surviving, we were warriors. It was about victory. All of our goals on the final exam was to have the best grade in the class. That was where we needed to go to get through that class. 1/2 of the final exam needed to be done without a calculator. The other half one could be used. I was in such a frenzy that I did the whole exam without the calculator. I was going to war and I was going to win, dam the torpedoes. I can’t remember exactly what I got on that test. A 96%? 97%. Doug probably beat me by a point. It was a long time ago. The thing is, Kirby did that. Kirby made all that happen.

That changed me. I knew I could do the paper work. I could do the math. It was all in my head.

Dan Kyle – I’ve been into motorcycles since I was about 19. As I mentioned earlier, I worked as a mechanic and a tuner. Still, it was just work then. In the early 2000s, I started looking at the bikes differently. I was taking the level of work that I had learned in Kirby’s math class to the whole motorcycle problem. I was digging deep, like Salvisberg. I was sharing this in online communities. There, I started chatting with Dan Kyle. Dan was pretty rad. A two time AMA tuner of the year and had a shop in Sand City. He was doing things the way I was trying to. We hung out a few times in his shop and exchanged several ideas. He was the real deal.

One thing that Dan said that I repeat often, “All the math and science in the world won’t tell you what will work at the racetrack, but they will tell you what won’t.” Amazing. The link between the empiricists and the theorists. This is what I took from Dan, do the math. Do the physics. Study the problem academically. That rules out the garbage that you don’t need to try. This is important.

Jim Lockheart, Roger Bland, and Barbara Neuhouser – At some point, I got a job with San Francisco State University in the Physics and Astronomy Department. I’ve been there for the past 15 years as a machinist for a group of research scientists. In academia, most of the people with PhDs are, in fact, stupid and certainly have no business in front of a class. Jim, Barbara, and Roger are exceptions. Jim is probably the smartest guy I’ve ever met, ever. He knew everyone’s job better than they did, rebuilt his own house, played in a rock band, and did some crazy science on gravity science satellites. Barbara is on par with Jim, insanely smart. She knows so much I couldn’t begin to understand. She built her own labs out and fought the system to get what she was due. A formidable woman when it was hard to be a woman in science. Roger is the reference for the scientist. He’s who I point to when talking about doing the work and doing it for love. He’s spent years working on experiments and ideas…and that’s after he retired. He just loves it and can’t stop. I’ve been lucky to be humbled daily by these folks.

Ronen Sarig – Now things go in reverse. I’m at my endgame. For the past few years, I’ve been riding with and talking about projects with Ronen. When first I met him, Ronen was a bit green but schooled well and extremely hard working. He had a few small projects under his belt including a good career start as an electrical engineer. Since, he has become a great mechanical engineer and done a wide variety of projects that span all sorts of understanding.

I did a lot of talking with Ronen about rigor and detailing work. He took a lot of that to heart, but not all. He’s still got a very hard head as I did when I was younger. The thing is, I’ve had to measure up to everything that I’ve told him. I have to work harder and harder to match him and prove my work. He’ll test me, he’ll call me out on bullshit. You don’t get that just anywhere, a friend who will tell you when you’re not passing muster. I just can’t let anything slide now and that’s because of Ronen.

In riding, I have to work very hard to stay faster than Ronen going down hills, but he’s going to pass me. He’s young and I’m old. The same goes for his projects and work. He is already far ahead of what I can do and is only getting better. At this point, Ronen is ahead of me and soon, I’ll be well beyond his rear view. Lost.

Those are just a few of the folks that stand out to me and how they may have effected me. We all need to make an inventory like this. We need to constantly re-contextualize what got us here and where we are going. Be grateful.

Pay it forward, pay it backward, just keep paying.

On Mentors:

Being a mentor is not about being supportive. It’s not about answering questions. It’s not about making anybody feel good about themselves. It’s also not about pretending that you know what you are talking about (especially when you certainly don’t).

Being a mentor is about getting a person from one side of the abyss to the other. About making the journey possible if the journey needs to take place. It’s about finding a way to get them to either quit or move forward, so the student doesn’t embark where they have no business.. It is, at it’s core, about having the honesty and wisdom it takes to produce change in someone.

A mentor isn’t supposed to answer questions, s/he asks them. A mentor doesn’t defend, s/he makes the student fight.

A mentor can be kind or cruel.

A mentor can be smart or dumb (but always wise)

A mentor might never tell a student anything the student wants to hear.

A mentor might only meet a student once or be there all of his/her life.

A mentor chooses the student and a student chooses the mentor. Both must affirm in the right mind or it is a farce.